Who Was She? Reclaiming the women history tried to bury.

Phillis Wheatley c.1753—1784

The first enslaved Black woman to publish a book in America. Eleven years later, she died in an unmarked grave.

You’re reading a byline that belongs to a woman right now. That was once unthinkable.

For a Black woman to put her name on a book in colonial America meant writing under constant suspicion and disbelief. Phillis Wheatley did it anyway.

That collision had an address: Boston, 1773.

Phillis Wheatley, aged 20, became the first enslaved Black American woman to publish a book.

Let’s be clear: Black women were writing long before anyone decided their words were worth keeping.

In 1746, at 22, another enslaved woman in Massachusetts, Lucy Terry Prince, learned that two nearby families had been killed in an Indian attack. She later turned that violence into a poem titled Bars Fight, named for “the Bars,” a colonial term for the surrounding meadows.

The poem didn’t live on paper. It lived in people. For more than a century, it was recited, remembered, and sung, surviving because memory had to do the work print refused to do. Bars Fight wouldn’t be published until 1855. By then, Prince had been dead for decades.

Prince’s words lived in memory. Wheatley’s would live in ink.

That difference is the story.

They Tried to Stop the Book Before the Ink Was Even Dry

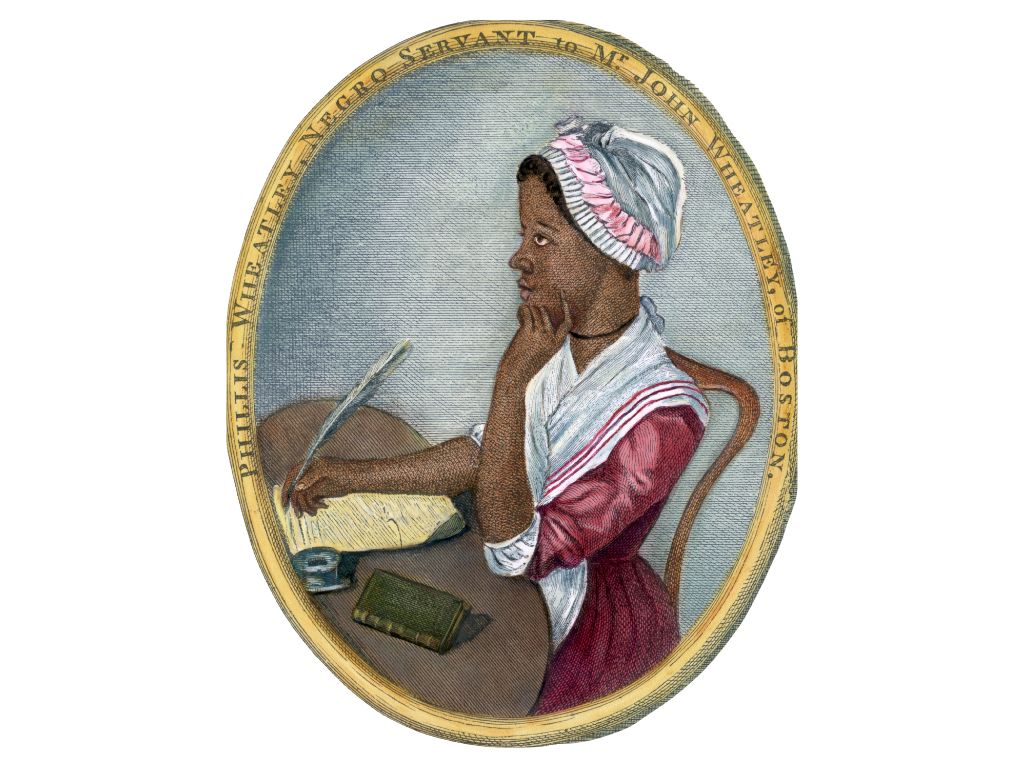

She was born in West Africa in 1753—and stolen before she was old enough to remember home. Shipped across the Atlantic on a vessel named Phillis (yes, that’s where they got her name), she was sold in Boston at 8 years old.

She arrived without English, and rewrote the language that enslaved her. When she demonstrated an exceptional mind, John and Susanna Wheatley taught her to read and write, exposed her to scripture and classical texts, and monitored the results. What they didn’t anticipate was that she would use that language to speak for herself.

At 13—while most of us were journaling our crushes—she composed On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin—a poem mourning two sailors who drowned off the Massachusetts coast. It was published in December 1767 in Rhode Island’s Newport Mercury.

Her fame grew in the colonies and across the Atlantic. But fame didn’t come without suspicion.

As her writing grew sharper—tackling salvation, liberty, and justice—a question echoed louder than the praise: Could a teenage Black girl really write this well?

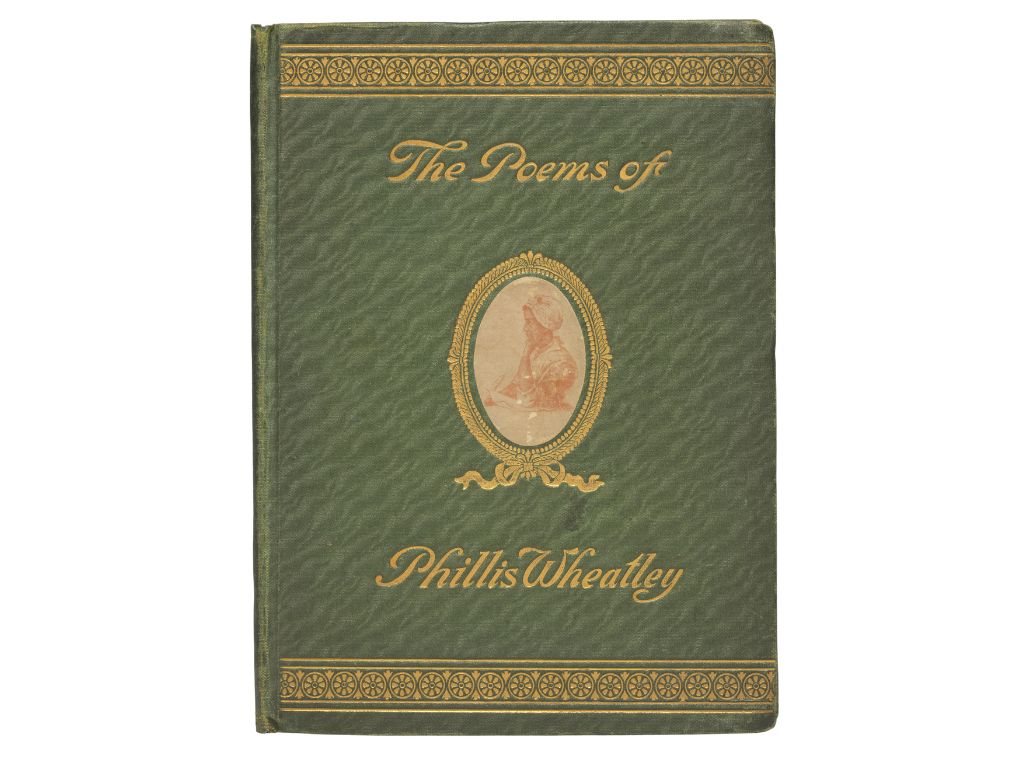

Wheatley was put to the test, literally, when she attempted to publish a book of her poems.

Printers in the colonies declined to publish a book that made their language of liberty look thin.

In England, Wheatley found an admirer, Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, who urged the London printer Archibald Bell to review the poems.

Bell agreed to publish, but only with verification that she wrote the poems herself.

To satisfy that demand, 18 of Boston’s most powerful white men, many of them slave owners, were gathered to decide whether a young Black woman could possibly be the mind behind her own words. They stamped her authorship as “authentic.”

Only after that approval did her book—Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral—get published in London later that year. Even then, her work wasn’t allowed to stand on its own. A signed statement from the Boston men ran in the preface and ads, an affidavit stapled to her name like genius came with a permission slip.

After her book was published, she was finally emancipated, likely thanks to pressure from her supporters in London. And she continued to write.

In 1775, she sent a poem directly to George Washington titled His Excellency, General Washington, praising the cause of the Revolution. An excerpt:

“Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the Goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! Be thine.”

He wrote back and invited her to meet him. He saw her mind. The new nation still didn’t.

Freedom didn’t translate into stability. In 1778, Wheatley married John Peters, a free Black lawyer and grocer. The following year, she planned a second collection of poems and advertised it repeatedly. But without white sponsors or institutional backing, publication was impossible.

The recognition she had once received evaporated. Daily life grew harder. Wheatley’s health declined. Two of her children died in infancy. Peters spent years in and out of debtor’s prison.

With a sickly infant son to support, Wheatley took work as a scullery maid in a boarding house, labor she had never been trained to do. It was a sharp descent from the literary circles that had once claimed her.

Wheatley died on December 5, 1784, at the age of 31, and was buried in an unmarked grave. Her infant son died soon after.

Her pen had shaken empires.

And still—America let her disappear.

She Made Space

Wheatley didn’t write alone. She created an opening.

Others stepped through it.

Maya Angelou turned verse into witness, using language to name Black survival—and forcing the nation to hear it.

Gwendolyn Brooks, the first Black poet to win the Pulitzer Prize, centered Black private lives on the page, compelling literary institutions to confront what they had long ignored.

Audre Lorde sharpened poetry into a political instrument, proving that words could dismantle silence rather than decorate it.

And Amanda Gorman, the first National Youth Poet Laureate, carried that tradition to a presidential inauguration in 2021, using The Hill We Climb to place a Black woman’s voice at the center of a divided democracy—and demand the nation listen.

This isn’t about ranking influence.

It’s about inheritance.

Because Wheatley put a book into the world while white men debated whether she was fully human, we get to claim authorship without permission.

We own our words. We sign our names. We push back when brilliance is called “difficult.”

While the founding fathers argued about liberty, a teenage Black girl printed it.

You didn’t forget her name.

You were never taught it.

That was always the plan.