A feminist origin story, a monster that outlived its creator, and why men have been explaining Frankenstein ever since.

Mary Shelley was just 18 years old when she began Frankenstein. Writing in the shadow of male peers who would go on to frame and reinterpret her work for centuries, Shelley created a story so enduring that men have felt compelled to revisit it again and again on film, often through the lens of their own ambitions and anxieties.

What would a preternatural feminist like Shelley—who began the story on a dare from her friend Lord Byron during a seance—say if she knew how often men would feel compelled to reinterpret her work in light of what she endured to write and publish it?

One of those men is Guillermo del Toro. A known Mary Shelley fan, his take on Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus may have set out to “capture the novel’s heart” by allowing us to empathize more with Victor—making his father an exacting, abusive surgeon, for example. But even so, del Toro’s rendition of Shelley’s story was so performatively gothy and gratuitously gory that it came off as inevitably, decidedly male.

A Daughter of Feminism, Raised to Question Men

To understand what inspired Frankenstein, one should take a closer look at Shelley’s own struggles with the concept of creation, maternal and fraternal abandonment, birth, and death.

Born in London to political philosopher William Godwin and the more successful writer, philosopher, and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, Shelley never really knew her mother, who died of what was known as puerperal fever (a type of sepsis) just 11 days after giving birth to her because the doctor called in to help remove the placenta didn’t wash his hands. It’s no wonder Shelley made Victor a doctor and a villain. To make matters worse, the woman Shelley’s father married soon after is said to have mistreated her.

Like The Creature she wrote, Shelley educated herself by escaping into the books she read and the stories she imagined. She’s said to have read her mother’s work all the time and, not only did it show her that writing was a path to personal liberation, but it also taught her to be a critical thinker, skeptical of men and their motivations—and that the sexual constraints of marriage were highly overrated.

Creation, Loss, and the Spark of Life

When Shelley wrote Frankenstein, she was partnered with Percy Bysshe Shelley, a radical and known atheist, and they’d already suffered the loss of two children. She’s said to have written, “Nurse the baby, read,” in her diary, day after day, until her child passed away on the eleventh day (just as her own mother passed 11 days after having her). “Find my baby dead,” she wrote, followed by another tragic diary entry: “Dream that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived.”

Prior to publication in early 1818, Shelley had lost her first baby; by late 1818, months after the novel’s publication, she had lost a second child. And the following year, she lost her third child. It’s no wonder she conceived of a story centered around a scientist’s obsession with what comprises the spark of life, and that Frankenstein’s Creature was meant to be regarded as so beneath him it remained nameless.

Anonymous, Questioned, and Still Unstoppable

Like her mother, Shelley was a progressive thinker and a feminist trailblazer, but the climate she lived in was just as inhospitable to such women. Her novel was a near-immediate hit, adapted for the stage just five years later, but, as she chose to publish anonymously at first, like most female authors of the time, she couldn’t bask in its success. Considering the book’s dark subject matter and how unsightly it was for a woman to have such thoughts back then, it was a very real fear that any children she had would be taken away from her.

Eventually, her husband wrote the foreword, and Shelley got her due. But for decades following, her authorship and rightful place in literary history were debated and called into question, so much so that she felt compelled to explain how she’d conceived of the book.

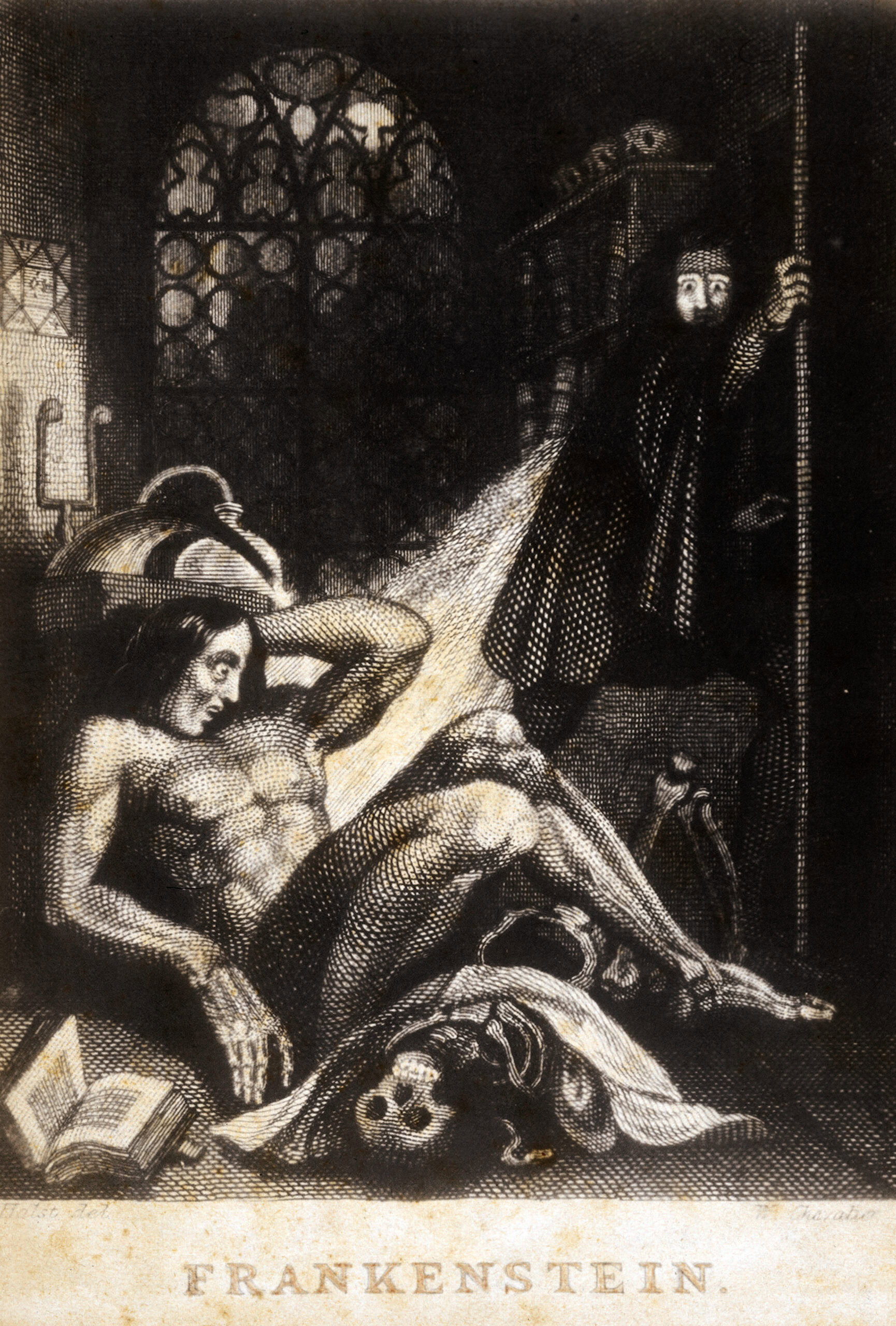

In the 1831 preface, she gets into how The Creature first appeared to her in a dream: “I saw—with shut eyes, but acute mental vision—I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.”

The Monster Men Keep Misinterpreting

According to The New York Times, “few works of fiction have inspired more adaptations, re-imaginings, parodies, and riffs” than Shelley’s enduring tale. The story of a man whose furious ego, hubris, and ambition drive him to hack life (as he can’t give birth) by any means, only to create murderous monsters that kill those who matter most to him (and anyone else in the way) is a plot that translates to the toxic masculinity and hubris in the quest for immortality we endure today—a sentiment del Toro was careful to preserve in his interpretation.

For example, though she ultimately remains subservient out of duty, he gave the character Elizabeth a defiance, a passion for entomology, and a feeling of mutual affection with The Creature, while the women in the book are misunderstood, silenced, and disposed of. It’s highly symbolic of how far we’ve come, which isn’t nearly far enough.

Giving Mary the Last Word

But in watching del Toro’s film, it’s not so hard to draw a straight line between a man tearing bodies apart to make a person and a woman being torn apart by childbirth. But there’s also a parallel between Victor’s macabre, mad scientist and his quest to make a person and Shelley’s macabre quest to write memorable characters, as both were determined to create something that endures far longer than they will.

Instead of ending his film with a quote from Byron, del Toro might’ve done better to conclude the film with Mary Shelley’s own words from the 1831 preface: “And now, once again, I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper.”

6 Responses

MS: Frankenstein taught me that it is okay to find tiny moments of joy, beauty, and shifts that become a balm during hard days. I had many causes for hard days, and this compassionate lesson from her book became both a balm and turned my hard days into days of honey. As a mother myself, I admire and appreciate that she gave the monster a name… Adam. ///

“Even broken in spirit as he is, no one can feel more deeply than he does the beauties of nature. The starry sky, the sea, and every sight afforded by these wonderful regions, seems still to have the power of elevating his soul from earth. Such a man has a double existence: he may suffer misery, and be overwhelmed by disappointments; yet, when he has retired into himself, he will be like a celestial spirit that has a halo around him, within whose circle no grief or folly ventures.”

― Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

Now we need a female director to make a film of Frankenstein.

Did Mary W.S. feel like SHE herself was “a murderous monster… (who killed everyone she valued)…” ? Because she blamed herself for her Mom’s death? I can’t remember what I learned in college…

But it IS clear she struggled to understand the more fatal elements of childbirth from both sides of the fence, in her personal pregnancies and in her writing. I feel so much for her. It was not an easy road to travel. And I feel bad for Mary Wollstonecraft for being cut short in the prime of her life too. Her work was doing amazing things for the time period. That is a loss in and of itself.

THANK YOU FOR WRITING THIS!

Thank you for the history and your perspective of one of the literary greats! Inspiring read that will keep me thinking for days.

Thoughtful observations on one of my favorite books. The movie is a visual delight, but you’ve nailed the nuances!